|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| The Rise and Decline of the Great American Corporation |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | ||

| Mar/01/2006 | ||

|

Clueless Turkeys The travails of the U.S. automakers have drawn attention, however fleeting, to the sorry state of U.S. manufacturing in general. The U.S. auto industry is the latest in a string of U.S. industries that were seen as pillars of the American economy, only to be submerged by some mysterious process of inundation. High-tech manufacturing, airplanes, computers and the like have succumbed to foreign competition. Like turkeys who don’t notice that all of their neighbors are being decapitated, American companies simply take note that, once again, something is happening without stopping to figure out if there are some larger forces at work. They fail to realize that no manufacturing industry can survive on its own; not only is the whole of the manufacturing sector greater than the sum of its parts, the parts without the whole will equal zero. The multinational corporations have bought into the idea that all they have to do is pursue profit, by whatever means necessary, in order to maximize both short-term and long-term profit and power. Thus does the invisible hand replace an all-powerful God with a flowing gray beard as the font of all that is good in the world, in the faith-based world-view of economists and CEOs alike. But unfortunately for both the corporate world and the U.S. economy, there is a profound contradiction between the pursuit of short-term profit and long-term viability. Manufacturing is going off a cliff, and the middle class is not far behind. When the middle class eviscerates, so will the main market of U.S. multinational corporations, and all the President’s military machinery will not be able to put that market back together again. The well-laid plans of the Walmarts and Dells of this world to make everything abroad and sell it at “home” will go up in smoke. The multinational corporations think that their brand is their most valuable asset, but Indians will buy from Indian companies, Europeans will buy from European companies, and Chinese will buy from Chinese companies. The thrill of buying American will be gone, and so will the American multinationals. The invisible hand will dump them into the dustbin of history. But surely these corporations are smarter than that, they must have some plan to deal with a shrinking American market? No. Advised by a class of professional economists who are trained to explain why this is the best of all possible worlds as long as the corporations can do whatever they want, blinded by greed and the low-hanging fruit of greater profits from lower wages, no CEO will think to do what Henry Ford did when he introduced the $5 day for workers. Ford justified his largesse by pointing out that his workers could now afford to buy his cars. Ford may not have been motivated by such far-sighted thoughts. He may have been trying to put a gloss on the need to increase wages so that the auto workers’ union would be undercut in its efforts to unionize Ford. Except in rare cases, top managers do not give up power unless the loss of decision-making is being forced down their throats, as in unionization efforts in the 1930s or regulation in the Progressive era or in the 1960s. When the corporations have their way, as in the Bush/Reagan/Clinton era, they manage to shoot themselves in the foot; NAFTA and Most Favored Nation status for China were good for them in the short-term, not in the long-term. The industrial economy as an ecosystem Destroying their market is one huge mistake; but there is something even more fundamental going on here. Ford and G.M. are at the top of the pyramid of the industrial system. If no man is an island then huge industrial companies such as Ford and G.M. have to be part of an entire continent. A former CEO of G.M. famously said that what is good for G.M. is good for America; but what he didn’t seem to understand is that what is good for the American manufacturing base is good, indeed critical, for G.M. A thriving economy that is based on a strong manufacturing base, such as the U.S. used to be, is a kind of ecosystem. For instance, in an ecosystem the plant-eating animals are dependent on the plants, and the meat-eating animals are dependent on the plant-eating animals and also indirectly on plants. In an economy, different parts serve different functions, and these parts are dependent on each other for survival and growth. The most important relationship in an industrial economy is that between manufacturers of final, consumed goods, and the machinery makers that provide the factory machinery that is used to make those final goods.

Production machinery is the critical technology in an industrial economy. Technological progress in production machinery is the foundation of economic growth. For example, the great strides in computer power that we have witnessed over the last few decades are the result of advances made in a particular class of production machinery called semiconductor-making machinery. In the auto industry, advances are dependent on various kinds of production machinery. For example, machine tools are used to shape and cut the metal pieces that make up most of a car. The more efficient the machine tools are, and the better trained the workers are to use the machine tools, the more precisely and quickly the car parts can be made, thus improving the quality of the cars while decreasing the cost. The economy that stays together grows togetherPaying unskilled workers less and less money is not the path to economic growth. The engineers who design the machines and the skilled production workers that make the machines are the people who drive technological progress and economic growth. If the machinery makers are disappearing, so eventually will the makers of consumer goods, because the consumer goods companies will not be able to obtain the best machinery in a timely manner. Since the Japanese and German machinery makers are thriving, then the German and Japanese consumer goods makers will get the latest and greatest machinery before the Americans. Even when they get them, the Americans will be at a great distance from their Japanese and German suppliers.   Distance is important in a manufacturing economy. Manufacturers need machinery makers and subcontractors that make the parts of the finished product. They need suppliers of raw materials and engineering consultants. All of these parts of an economy form a cooperative system. The market is all about competition; production is all about cooperation, and cooperation works best at close quarters. The engineers need to “kick the tires” of the new production processes they design. So while a market may be global, production and the growth of production take place most efficiently at continental or subcontinental distances. A system of production is Japanese, or European, or Indian, or American – unless that production is scattered to the four winds. The U.S. multinational corporations have not only scattered their production all across the planet, they have stood by while the American machinery makers have been slaughtered by foreign competition. Almost all of the remaining machine tool makers in the U.S. are foreign owned. American engineers probably won’t visit the factory that makes the goods they are designing or spend time talking with the machinery makers’ engineers. Both of these activities are crucial to a competent engineering class. Losing the forest and the treesNo wonder Ford and G.M. are not known for innovation and quality. Most observers blame the automakers’ decline on some kind of historical inertia created by the dominance that these firms wielded for so long. Certainly, that may have something to do with it. But these observers miss the importance of the ecology of the industrial system because they understand marketing and finance, not production. Ford’s “world” cars are “bad” cars precisely because they are “world”. Ford used to have a huge, centralized production complex in River Rouge; if they really wanted to turn things around, they would go back to their roots.

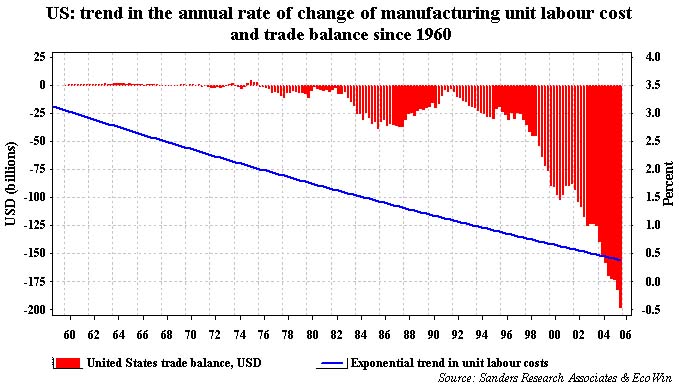

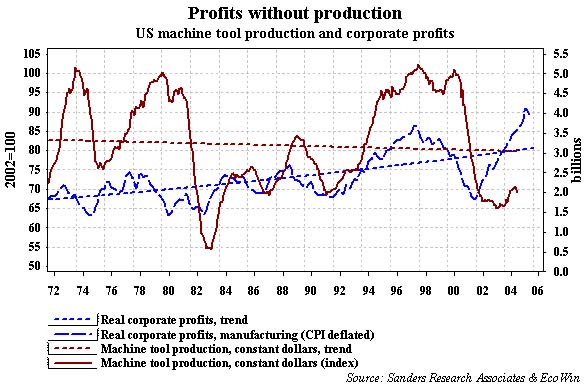

The industrial ecosystem that the car companies depend on needs to be a certain minimal size. An economy needs a thick growth of small machine shops and parts suppliers in order to support the stands of large industrial companies such as Ford and G.M. A similar principle has been discovered for natural ecosystems. For instance, it has become clear that isolated parts of the Amazon rain forest need to be of a certain minimum area if they are to sustain most of its species. If the rain forest is left as a checkerboard of open spaces alternating with rain forest, and the “checks” that are rain forest are too small, then they will not be viable, and they will eventually disappear. The same principle holds for an industrial ecosystem. This is the deepest problem for the car companies. They cannot hang on if they are the only existing part of the manufacturing sector. Like a clump of rainforest that is too small, they will eventually disappear, unless they are reconnected to a large, thriving manufacturing sector (see my previous article, “Before the economy hits the fan”, for a discussion of how this can be done). The general problems of the manufacturing sector have been caused by three main problems: cheaper labor abroad, a military-industrial-complex at home, and the transformation of industrial firms into financial and marketing firms. Expensive workers are good for youThe problem of cheaper labor abroad has been treated as if it was a problem with no solution. There is simply nothing that can be done, one reads, which means that the American working and middle classes are doomed. If the cost of labor were indeed the main consideration in production, this would be true. But it most emphatically is not true. The central factor in the creation of economic wealth and growth is not the cheapness of labor, but the productive power of machinery. If cheap labor were the road to international competitiveness, then the oversupply of near-starving peasants in China and India would have kept them at the top of the world food chain for the last 1000 years. When England first invented industrial machinery, it was able to use this advantage to conquer one third of the world’s surface. When the English decided that empire was more important than industry, the U.S. took over the global economy, until it now, as the Mother country once did, has become blinded by empire. But while it was on top, until the mid-1970s, the U.S. consistently paid the highest industrial wages in the world. According to the late Seymour Melman (he was a professor of industrial engineering at Columbia University), this fact actually helped the U.S. maintain its lead.  Melman’s concept that explained this unconventional wisdom he called “alternative cost”. The basic idea is this: faced with high labor costs, firm managers will be more willing to mechanize, that is, use more machinery, and more sophisticated machinery, instead of using labor. By using more, better machinery, they increase labor productivity, which leads to higher wages, and they also stay at the cutting edge of technology. Melman compared factories in England and the U.S. after World War II, and found that the English, who paid lower wages, were using more primitive equipment than the Americans[1] . Melman’s insight almost led to his dismissal from Columbia University, because a conservative professor was offended by the idea that the economy is improved by giving higher wages to workers; the implication was that unions, by keeping wages high, were actually good for the economy. An eminent statistical economist came to his defense, and Melman was able to spend the next half-century doggedly pursuing his conviction that less military and more labor power was better for the economy. Melman also argued that the productivity of capital is more important than the productivity of labor. If machines are central to the process of production, and if the machinery costs millions of dollars, then it makes sense that keeping machinery running as efficiently as possible is more important than the exact number of workers one is using or even how much they are being paid[2] . By driving down the price of labor in the U.S., manufacturing companies have reversed the power of “alternative cost”. Instead of using more and better machinery, they think it is easier or cheaper to move production to a country such as China. As a result of this process, the general level of competency of a country’s manufacturing firms will decrease. Voila, the U.S. has a huge and growing trade deficit in manufactured goods, because American manufacturers are losing the competence to produce.  So higher wages were a competitive advantage, not a disadvantage (not to be confused with comparative advantage, the subject of another essay). The Chinese are not doing themselves any favors by keeping their wages low either, because this will suppress their technological progress. A permanent war economy is a permanent drag on the economyThe other huge drag on American manufacturing competence has been the large, and now even larger, military-industrial-complex. Melman showed how this process works in gory detail. One way to demonstrate a theory in social science is to pick a case study that combines variables in a unique and useful way. If we want to see the effect of the military on civilian work, then a good case study is to see how defense companies perform when they attempt to do civilian work. Melman showed that when defense firms have attempted to enter the field of making buses, people movers, or subways, the products were unusable. They were much too expensive, broke down all the time, did not perform up to standards, and were not delivered on time.[3] These are all hallmarks of incompetence, the kind that the Soviets were famous for in their civilian sphere. The reasons are similar; like the American military-industrial complex, the Soviet economy was basically a system for producing military equipment. When firms are not subject to the discipline of selling their products in a market, then they do not learn how to make as much as possible, as well as possible, for as cheap as possible. The U.S. Pentagon is the American equivalent of the Soviet Gosplan, their central planning agency. This lack of competence spills out into the rest of the economy. Because the military pays better salaries than the civilian sector, many of the best and brightest scientists and engineers enter the military sector and learn bad habits. Whole firms, or divisions of firms, are also drawn to the higher profits guaranteed in the military sector as moths to a light. Corporate Chesire CatsEven G.M. and Ford feed at the military trough. With the civilian part of manufacturing firms looking over the oceans for cheap labor, and the military side of manufacturing firms looking for lucrative government contracts, when the consumer comes knocking, nobody is home. Or rather, as G.M., Ford, and even G.E. have shown, there is one face that they are more than willing to show to the consumer: the financial face. All three companies make more from financial subsidiaries than from producing. For instance, in 2004, Ford made a profit of $5 billion from finance, and a loss of $177 million from automobiles[4] , and in 2004 G.M. made almost $3 billion on finance and lost $89 million on cars[5] . Finance, then, becomes the third nail in the coffin of U.S. manufacturing, after cheaper wages and military contracts. Making “profits without production”, the title of one of Melman’s books, became possible when large manufacturing corporations turned into large financial firms. In the 1980’s, U.S. Steel used its profits to buy an oil company. Cisco doesn’t make its products, acting as a combination of finance, marketing, and design. Dell contracts with companies all over the world to make its parts, and only performs the final assembly in Texas. When the dollar collapses and the cost of these outsourced parts become prohibitive, Dell’s business model will go back to the garage from whence it came. Manufacturing and myriad other “high-tech” firms have become the chesire cats of the economy, losing everything but their brand. But a brand is tied to a particular economy, and when the American economy goes, so will the brand. The U.S. car companies are victims of their own protectionist lobbying, because car companies are now prevented, via “voluntary import restraints”, from outsourcing all of their work. Toyota and Honda are doing just fine in the U.S., but most of the work is for assembly, a technologically sterile endeavor. The process of thousands of drones repetitively attaching the same car part over and over is not the heart of the industrial process, but the end point. Toyota and Honda make the most sophisticated parts in Japan, but Ford and G.M. cannot simply create an entire automobile industrial ecosystem in another country. The automobile ecosystems have taken a long time to put together, particularly in Germany and Japan. Their automobile industries are embedded in the wider German and Japanese industrial ecosystems; G.M. and Ford have to sink or swim with the American one.  The pension problems of these companies are really the consequence of their decline, because a company that is growing will be able to offset the retirement costs of their older employees with the greater gains that they are supposed to be making with their new employees. The health care problems, which allegedly add over $1,000 to the price of each car, can be seen as a consequence of the primitive nature of the U.S. industrial economy. If a national industrial system should be considered as a whole, than the wider problems of health care, education, and the infrastructure must be considered when assessing the performance of any part of the wider system. All three of these pieces are the poor stepchildren of the main beneficiaries of the Republican Monarchic Restoration, the military-industrial complex, the most wealthy taxpayers, and their partners in corruption. It is on the shoulders of the electorate to shift from one set to the other; the corporations are too busy following their noses. You can contact Jon Rynn directly on his jonrynn.blogspot.com .

You can also find old blog entries and longer articles at

economicreconstruction.com. Please feel free to reach him at

This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need

Javascript enabled to view it

. [1] Melman, Seymour. 1956. Dynamic Factors in Industrial Productivity. Oxford: Blackwell [2] Melman defines productivity of capital by “the total time of machine working, by stabilizing the rate of working, b reducing defective output and by minimizing unscheduled interruption”. From Melman, Seymour. 2001. After Capitalism. New York: A.A. Knopf. p. 425 [3] Melman, Seymour. 1983. Profits Without Production. New York: A. A. Knopf. p. 253-259 [4] Ford 2004 Annual Report, p. 54 [5] G.M. 2004 annual report, p. 44 | ||

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|

American

companies fail to realize that no manufacturing industry can survive

on its own; not only is the whole of the manufacturing sector

greater than the sum of its parts, the parts without the whole will

equal zero... But surely these corporations are smarter than that,

they must have some plan to deal with a shrinking American market?

No. Advised by a class of professional economists who are trained to

explain why this is the best of all possible worlds as long as the

corporations can do whatever they want, blinded by greed and the

low-hanging fruit of greater profits from lower wages, no CEO will

think to do what Henry Ford did when he introduced the $5 day for

workers. Ford justified his largesse by pointing out that his

workers could now afford to buy his cars.

American

companies fail to realize that no manufacturing industry can survive

on its own; not only is the whole of the manufacturing sector

greater than the sum of its parts, the parts without the whole will

equal zero... But surely these corporations are smarter than that,

they must have some plan to deal with a shrinking American market?

No. Advised by a class of professional economists who are trained to

explain why this is the best of all possible worlds as long as the

corporations can do whatever they want, blinded by greed and the

low-hanging fruit of greater profits from lower wages, no CEO will

think to do what Henry Ford did when he introduced the $5 day for

workers. Ford justified his largesse by pointing out that his

workers could now afford to buy his cars.